If I interrupt my planned posts on algae, you better bet it’s something amazing.

I’m pre-writing my blog at the moment, so by the time this is up and online it’s been a couple of days or so. But the story goes that on Saturday, December 2, I collected water from a new puddle at Renfree Field in Sacramento, and I’d been observing it for about a day or so, when all of a sudden, I made the discovery of a gigantic rotifer on Sunday evening. Remember my previous pictures of other rotifers at 100x? This is a picture of this rotifer at 100x…except it is so large, only its mouth can fit in the frame:

After frantically scouring the web for about an hour or so, trying to discover what it was, I finally happened upon what I think is the right organism: Asplanchna silvestrii.

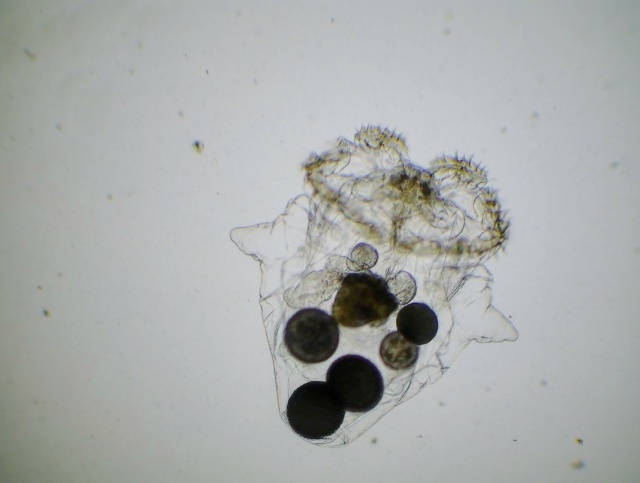

First described in 1902, A. silvestrii is one of the largest species of rotifers in the genus Asplanchna, and possibly in the entire phylum Rotifera (it’s a close call between it and its close relative, A. sieboldi) – the largest specimens of both species can reach over 2 millimeters in length! The genus Asplanchna is rather unique among rotifers, as it contains several species which are active predators. Most rotifers peacefully swim through the water column filter-feeding on small bacteria and algae with their cilia; Asplanchna hunt by swimming through the water and feeling around for nearby smaller rotifers, their preferred prey. When their head touches another rotifer, they quickly open their mouths, suck their prey in, and snap their jaws closed, trapping the rotifer in their stomach. In addition to small rotifers, Asplanchna can also eat large single-celled protozoa such as Paramecium, and will also tackle the larva of crustaceans like copepods and cladocera. My individual, I suspect, eats small Epiphanes senta that live with it in the puddle water, and I also noticed its gut contents have Eudorina algae (which it later vomited out when stressed on the microscope slide).

Asplanchna is heavily studied for its predatory behavior, and what scientists have determined is that how much and what type of food is available is often intricately connected with the size and shape of the adult animal. The species A. silvestrii, A. sieboldi and A. intermedia all exhibit what is called phenotypic plasticity, meaning that individuals of the same species can have multiple adult growth forms, named after the general appearance of their body. The smallest form, the saccate, appears sort of round but with a flat head (a little more curved than a semicircle), and is usually around 500 microns in length; it is the first morphotype to appear when dormant eggs hatch. The largest and latest-stage form which can reach over 2 millimeters in length is called the campanulate (from the Latin root meaning “little bell-shaped”), and as its name implies it looks rather like the body of a hand bell. The medium-sized form is the one I found – it’s called the cruciform and is shaped very roughly like a cross. (My individual measured about 1.4 millimeters in length and 0.75 mm in width – right in the middle of the average length of 1-1.7 mm for this form.) When its rotifer prey begins to fatten up and eat algae, cruciforms begin to appear in the sample. However, I don’t think this is as great a name for the growth form as my own, the “winged form”:

As you can see, the little nubs on either side of the main body of the rotifer do look sort of like manta ray wings…if a manta ray had pathetically tiny T-rex like wings. A better description might be like that of a sea angel, but not many people have seen those.

Although I don’t know much about the habitat and distribution of these giant Asplanchna, I don’t think my discovery was too particularly unusual. The one study that I’m mostly referencing here involved collecting and culturing A. silvestrii from Little Fish Lake in Nevada, which was described as being endorheic (where water flows and collects inland, rather than into a creek and eventually out to sea) and seasonally very salty. It’s not a stretch to imagine how A. silvestrii could have survived in a smaller puddle here – it seasonally refills with water too, and as the water evaporates it is likely to increase in concentration of minerals and salts.

Although this find wasn’t necessarily groundbreaking and revolutionary, it was definitely very awesome for me. I’ve seen Asplanchna in samples of lake water before, but this was the first time I’ve found one so large and with this very distinctive form. Based off of my image searches, very few photographs have been taken of either A. silvestrii, A. sieboldi or A. intermedia in their cruciform stage (most of the reference images are hand drawings from the 1900s), so I believe that this is still a scientifically useful recording. I’ll be sure to keep an eye out for more of these individuals, and if I can find them again I will try to collect one for doing some DNA work eventually. Stay tuned.

Works cited:

Gilbert, J. (1973). Induction and Ecological Significance of Gigantism in the Rotifer Asplanchna sieboldi. Science,181(4094), 63-66.

Hampton, S., & Starkweather, P. (1998). Differences in predation among morphotypes of the rotifer Asplanchna silvestrii. Freshwater Biology, 40(4), 595-605.